It all began as an experiment.

Could a major railroad advertise itself advantageously via

the fledgling medium of commercial radio?

The radio series had been on the air for two full years.

Response seemed quite good: listener polls regularly showed Empire Builders in the top tier of

broadcasts aired on Monday evenings, and even appeared among the leaders across

all radio programming; unsolicited fan mail gave anecdotal evidence of a

sizable following of devoted listeners; and response was strong whenever a

special booklet or giveaway was offered during one of the Empire Builders programs.

Despite indications of the success of this radio advertising

campaign, Great Northern Railway management continued to speculate as to the

actual positive impact on revenues. Were freight receipts higher, and was there

any increase in passenger revenue? And if so, to what degree could such

successes be attributed to the singular impact of their radio campaign? After

all, while goodwill is an important asset for any company, ultimately they

wanted more businesses shipping goods and more people riding Great Northern

trains. Increased traffic to Glacier National Park was particularly desired,

what with the GN’s hotel subsidiary operating virtually all the lodging facilities

in or near the park.

And so, as this grand experiment in radio advertising wound down to its conclusion, one last experiment was attempted. A new question emerged: Would radio listeners respond to an offer to tour Glacier National Park in the company of one of the stars of the Empire Builders radio show?

And so, as this grand experiment in radio advertising wound down to its conclusion, one last experiment was attempted. A new question emerged: Would radio listeners respond to an offer to tour Glacier National Park in the company of one of the stars of the Empire Builders radio show?

|

| Passenger Traffic Manager of the Great Northern Railway, A. J. Dickinson. |

On January 15, 1931, the GN’s Passenger Traffic Manager,

A.J. Dickinson, issued Passenger Traffic Department Circular #16-31. This

communique to all General, District, and Traveling Passenger Agents announced

that on the Empire Builders broadcast

of Monday, January 19th, plans would be unveiled for an “Old

Timer’s” Tour of Glacier National Park. The plan was to offer a deluxe 10-day

all-expense paid tour of the park, to be hosted by none other than actor Harvey

Hays – the “Old Timer.” At the outset, this plan was touted as an experiment to

find out what level of interest could be generated for such a tour among the

listeners of the weekly radio show. The tour was not advertised via any other

vehicle than the opening and/or closing announcements of this weekly 30-minute

broadcast. Once the responses to this announcement started coming in, Dickinson

and his staff would be able to decide how to proceed with the tour, whether

that meant one tour, many tours, or none at all.

The broadcast of January 19th was a drama titled

“Nan o’ the Northwest.” The story was set in Glacier National Park. As the

program opened, announcer Ted Pearson had an exchange with the Old Timer about

the idea of hosting a tour of the park in the summertime. Although Dickinson’s

passenger department circular was vague on the timing of any tours, the dialog

in the radio show immediately targeted the 4th of July.

For your listening and viewing pleasure, I have created a

couple of A/V clips using the original broadcast audio. The first clip has the opening,

and the second clip the closing, of the January 19, 1931, broadcast. I’ve paired this

audio with an appropriate collection of vintage film footage and associated

still images. Please note the audio is in poor shape in places. Also, a few of

the still images are not strictly of the same vintage as the broadcast, but

should at least provide a nice visual representation of the audio content.

The Old Timer’s invitation to join him on a ten-day trip through Glacier Park proved to be an enticement that many found hard to resist. For a variety of reasons, they picked up paper and pen and wrote to the Old Timer, care of the Great Northern Railway, Chicago, Illinois. Such letters arrived by the bushel. On January 22nd Harold Sims wired Ralph Budd, the president of the Great Northern Railway, to report the early returns. Sims told Budd that the railroad had already received 341 inquiries to date. During the broadcast of January 26th, the Old Timer lamented he was receiving too many replies – he couldn’t take them all.

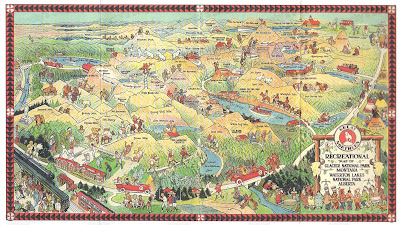

Those who wrote to the GN asking about the Old Timer’s Tour

were sent a 6-page itinerary of the trip, along with a copy of a

comical map of Glacier Park, illustrated by Joseph Scheuerle. The itinerary laid out the details of what was in store for the tour’s participants from the day they arrived at Glacier Park Station until they departed, ten days later. Here is a synopsis of some of the activities planned:

comical map of Glacier Park, illustrated by Joseph Scheuerle. The itinerary laid out the details of what was in store for the tour’s participants from the day they arrived at Glacier Park Station until they departed, ten days later. Here is a synopsis of some of the activities planned:

|

| The Empire Builder at Glacier Park Station. Photo by George Grant. Courtesy National Park Service, West Glacier, Montana. |

Day 1 (July 1): Arrive Glacier Park Station at 12:15pm; eat lunch; drive

in tour coaches up to Two Medicine Chalets; ride across Upper Two Medicine Lake

on the launch “Rising Wolf” and take a short hike to see Twin Falls. On the

return drive, the coaches stop for another short hike to see Trick Falls.

Dinner at Glacier Park Hotel; evening entertainment by Two Guns White Calf and

fellow Blackfeet Indians (with a few ceremonial inductions into the Blackfeet

tribe); remainder of the evening at “Mike’s Place” in the town of Glacier Park

Station.

Day 2 (July 2): Breakfast at the hotel; depart at 8:15am for

a 55-mile tour coach trip to Many Glacier Hotel. Lunch at hotel; short saddle

horse trip to see Grinnell Lake; dinner back at Many Glacier Hotel; launch ride

across Swiftcurrent Lake and Lake Josephine; bonfire on the lakeshore with

wiener roast; return to hotel. Dancing at the hotel for those who aren’t yet

too sleepy or too tired.

Day 3 (July 3): Breakfast at the hotel; head out on 17-mile

saddle horse trip to Crossley Lake (aka Cosley Lake) Dude Ranch; horseback ride

through Ptarmigan Tunnel

(dedicated by the Old Timer); spend the night at the dude ranch.

Day 4 (July 4): Breakfast at the dude ranch; ride saddle

horses over Indian Pass to Goat Haunt Camp (south end of Waterton Lake); ride

the launch “International” to the Prince of Wales Hotel at the far end of the

lake, in Canada. Dancing at the pavilion in the town of Waterton; more

entertainment and refreshments* at Prince of Wales Hotel before turning in.

|

| Harvey Hays at the head of the pack train - on the trail in Glacier Park. T.J. Hileman photo. Courtesy National Park Service, West Glacier, Montana. |

Day 5 (July 5): Breakfast at Prince of Wales Hotel; motor car ride to Cameron

Lake; return to hotel for lunch; motor car ride to Cardston; motor south across

the international boundary to St. Mary’s Lake, a trip of 75 miles. Catch the

launch “St. Mary’s” for a 10-mile trip to the Going-to-the-Sun Chalets for

dinner; after-dinner boat ride up the lake to view mountains Red Eagle, Little

Chief, Almost-a-Dog, Reynolds, Going-to-the-Sun, etc. Return to

Going-to-the-Sun Chalets for a little entertainment and then turn in.

Day 6 (July 6): Breakfast at the chalets; pack lunches for

saddle horse ride up over Gunsight Pass to Sperry Chalets; lunch on the trail;

dinner at Sperry Chalets.

Day 7 (July 7): Hike out to Sperry Glacier; return to the

chalets for lunch; go on 7-mile saddle horse ride to Lake McDonald Hotel. After

dinner, take a moonlight cruise on the launch “De Smet” around upper end of

Lake McDonald; return to Lake McDonald Hotel for an evening party in the hotel

lobby.

Day 8 (July 8): Breakfast at the hotel; auto coach ride up

to Logan Pass over “the new Inter-Mountain Highway.” Lunch at Logan Pass;

saddle horse ride across the Garden Wall to the Granite Park Chalet.

Day 9 (July 9): Morning hike to the top of the Garden Wall

and directly above Grinnell Glacier. Back to the chalets for lunch; saddle

horse ride to Many Glacier Hotel via Swift Current Pass. Dinner at Many

Glacier, and “a farewell party that will linger in your memories for a long,

long time.”

Day 10 (July 10): Breakfast at Many Glacier Hotel; automobile

ride to Glacier Park Station; lunch at Glacier Park Hotel; depart on the Empire

Builder train, with Chief Two Guns White Calf and fellow Blackfeet, plus cowboy

guides, bidding the travelers farewell.

* The Fourth of July was to be spent at the Prince of Wales Hotel in

Canada – those “refreshments” undoubtedly included alcohol, which was still

prohibited in the U.S.

The entourage was to be accompanied by a chaperon-hostess, a

National Park Service Ranger and a nature guide, and at least one

representative of the Great Northern Railway. The trip proposal included this

wishful statement: “I’m hoping to have some of the folks you have heard on “Empire

Builders” with me, so you can meet them in person.” To my knowledge, the only

performers from the radio series who participated in any way were actor Harvey

Hays (the Old Timer) and Marc Williams (the “Cowboy Crooner”). Williams

appeared on a handful of Empire Builders

broadcasts in the final season, primarily to sing a few of his western songs.

Here is a sample of the singing of Marc Williams:

Here is a sample of the singing of Marc Williams:

The team at the Great Northern Railway responsible for

organizing this massive undertaking was concerned about the size of the group.

They had to limit the participants to forty, at most. Any more than that would

be unwieldy, and delays along the trails would be inevitable. It was also

paramount that participants be reasonably fit, and capable of keeping up a

steady pace.

The cost of this ten-day tour of Glacier Park (all in, with

meals, lodging, transportation in the park, entertainment, etc.) came to $200.

Participants still had to get themselves to and from the park, and were of

course assisted with making reservations to ride round trip on the Empire

Builder.

About two weeks after the tour was first publicized, Ralph Budd

was ready for an update. Sims wrote to Budd on February 7th and reported the

magnitude and tenor of the responses.

Answering your inquiry, I

estimate that about half of the inquiries that were received about the Old

Timer’s vacation were from children, persons who were actuated by no motive

other than curiosity, and persons who weren’t financially able to make a

western trip.

The other half appear to be real

prospects for some sort of a trip over the Great Northern. Probably more than

half of such inquiries represent two or more persons.

There have been seven deposits

made already – and there are six or eight other tentative reservations.

A few respondents were employees of other railroads, and had

passes to ride for free. They were excluded from the early process of securing

participants, as it was preferred to include patrons who would be paying to

travel to and from Glacier Park on Great Northern trains.

Sims added that the GN Traffic Department staff were

“feeling our way along very carefully in this, and are not going to take it up

on the radio again until the week after next.”

At the beginning of the Empire

Builders program of February 16th, the Old Timer once again

commented on having “too many” people writing about the trip. Announcer Ted

Pearson declared this must be good news – the party of 40 was accounted for.

The Old Timer said “Forty? Forty, and then some I guess, Ted.” Pearson challenged

the Old Timer on this point, reminding him he said they could only take 40

participants on the tour. The Old Timer then asked, “I can take more

than one vacation, can’t I? I don’t aim to disappoint any of my friends, if I

can help it. But I tell you Ted, I guess we’ll just have to fix up more than

one trip.”

During the closing of the February 16th

broadcast, the size and number of Glacier Park trips was addressed once again.

ANNOUNCER: Say, Old Timer – have you got our vacation

all figured out yet?

PIONEER: (chuckles) Well, every one of the

days is all figured out in black and white, Ted, right here.

ANNOUNCER: And you’re going to take another party of

forty – that’s fine! And that means that

some of your radio friends that couldn’t have gone with you otherwise can go,

doesn’t it?

PIONEER: Yes, that’s the idea, Ted. So all of

my friends, who want to go, have to do to find out about this vacation trip is

to write me, care of the Great Northern Railway, a hundred and thirteen, south

Park Street, Chicago. Then I’ll write back and tell ‘em all about it

No promise was actually given to conduct more than one trip.

This was, in a way, a ploy to encourage people to continue writing to the

railroad. Even if participation of prospective tourists on this particular trip

fell through, the railroad felt it could reach out to them concerning other

visits to Glacier Park.

A new circular to the company’s travel representatives,

Circular 80-31, was issued on February 26th. In it, Passenger

Traffic Manager A.J. Dickinson reported nearly 2000 inquiries about the Old

Timer’s Tour had been received to date. He shared the tentative plan to arrange

two or three additional parties to accommodate this unexpectedly large amount

of interest. Tour dates were suggested as July 15, August 1, and August 15. Dickinson

acknowledged in this circular the awkwardness of how they must proceed. He

warned that this information was not to be divulged yet in any detail to the

traveling public. He outlined his concerns:

There

are several reasons for this:

1)

We do not wish to commit ourselves for the

expense involved for less than a complete party

2)

We think that the appeal of accompanying the Old

Timer on a vacation, to many people at least, is its novelty an exclusiveness,

and that it would be detrimental to say or do anything that would tend to

commercialize it, and

3)

The advertising that has already been done has

been in conformity with this idea of exclusiveness, and it will be necessary to

make future radio announcements consistent with what has been said before.

One angle Dickinson proposed to the ticket agents was to

target the parents of recent college graduates. As Dickinson stated, “a trip to

the park with the Old Timer would appeal to many parents who wish to give their

children some kind of a graduation gift.” Dickinson added that if at least two

or three tour parties could be filled up, “we will probably keep the Old Timer

at the park all summer… and almost everybody who visits the park this summer…

would be likely to run into the Old Timer at one of the hotels.” Harvey Hays

suffered from hay fever. He most likely would have enjoyed an opportunity to

spend the entire summer in Glacier Park under some sort of employment contract.

However, it sounds like Dickinson was making plans for Hays that the actor was

not privy to at that point.

Harold Sims updated GN President Ralph Budd on February 28th,

outlining his thoughts about the Old Timer’s Tour, and general prospects for

increasing travel to Glacier Park. The Great Depression created hard economic

times, yet these businessmen were determined to scrap for every travel dollar

they could find and attract to their railroad. Remarkably, Sims was still

optimistic that the Old Timer’s Tour had ample interest to fill out multiple

tour groups. He wrote, “after getting sufficient reservations to feel assured

of three or four parties for the Old Timer, I want to push an eight-day tour of

the park, following the Old Timer’s itinerary except for omitting the last two

days.” Sims had the idea multiple tours could set out from Glacier Park Hotel

“shotgun” style, one group starting out a day after the group before.

Naturally, the Old Timer himself could not host all of them, but Sims argued

such tours had several advantages over other travel options. He asserted such

tours would be superior to the typical dude ranch experience; other tours of

national parks did not feature trail trips; exposing tourists to the wilds of

Glacier Parks mountain reaches would create perpetual boosters of them; and

that such well-organized tours were desirable to many tourists who would not

otherwise be compelled to get out to see and do so much.

Sims then pitched a “quota plan” to Budd. He said by using

available statistics from the 1925 summer tourist season, ratios could be

determined for the ridership numbers generated by each ticket office or other

sales point. He proposed that these railroad ticket agents be challenged to

meet or exceed the same numbers their offices produced six years earlier

(before the infamous 1929 stock market crash, and the subsequent onset of the

Great Depression). As if all the ground work and heavy lifting had already been

done for them, these ticket agents would be reminded of “the expensive

promotional work that has been done, including radio, and the necessity of

showing commensurate returns.” Sounds like he was proposing that the floggings

would continue until morale improved. It seems Ralph Budd recognized the folly

in setting such unrealistic goals. Still, it was among Sims’ duties to apply

the advertising of the company in a meaningful way, to produce tangible

results. You can’t fault the guy for trying.

As the weeks went by, the Empire Builders radio broadcast continued to provide updates about

the Old Timer’s Tour. Although it was reasoned that with enough response there

could be two or more tours over the summer, ultimately there was just enough

participation to conduct a single trip. Mr. Budd was notified on May 27th

that, to date, a total of 15 definite reservations had been made, with

deposits, and several others looked like strong prospects. The expectation at

that point was to have a party of about 20.

Over the last few weeks that Empire Builders remained on the air, brief reminders of the Old

Timer’s Tour were offered, usually within the closing announcements. In the

week following the final broadcast of Empire

Builders, a trio set out to Glacier Park to begin making last-minute

preparations. This group consisted of Harvey Hays, Marc Williams, and O.J.

McGillis. McGillis was the Great Northern Railway’s Manager of Advertising and

Publicity. Among other tasks, the three needed to get in a little trail riding,

so they might not be too saddle sore when the tourists arrived to join them.

In a Naturalist’s Monthly Report made in July, 1931, several

of the park rangers and naturalists who supported the Old Timer’s Tour were

identified by name. Among them were: Dr. J.V. Harvey, Stephen Thomas, Ranger

Naturalist Wilson, and Ranger Naturalist Bailey.

|

| Press photo from 1931. Typed info on back on photo states "View taken from the tunnel shows member of the Old Timer Empire Builder party looking at Heaven's Peak." |

|

| Harvey Hays leads the Old Timer's Tour on a trail in Glacier Park. T.J. Hileman photo. Courtesy National Park Service, West Glacier, Montana. |

It is unclear how many of the Old Timer’s reported “twenty-six

nature-loving companions” were paying participants, and how many of that number

were railroad or park service employees. One other source, an article from the

Lethbridge Herald of July, 1931, attempts to list the names of all the

participants as they approached Waterton and the Prince of Wales Hotel on July

4th. Unfortunately, the only copy of this information currently at my disposal

is one that appears to be an OCR rendering of the original news article. Some

of the text is garbled. However, the list includes O.J. McGillis of the Great

Northern Railway, Harvey Hays, Marc Williams, and an additional person, park

ranger Ross Jordan. There appear to be another 24 individuals accounted for.

Unless I find cause to write some more about the radio

series (and I certainly might, you never know…), this will probably be the last

of my blog entries about Empire Builders.

Please use the email address shown in the banner at the top of this page to

contact me about ANYTHING concerning the Empire

Builders radio program. Seriously. Write to me.