The Empire Builders

episode of March 25, 1929, featured a dramatization depicting the exploration

of the northwest United States by Pierre Gaultier de Varennes, sieur de La

Vérendrye (11/17/1685 to 12/5/1749).

His quest for the Pacific Ocean took place

in the 1740’s. Verendrye and his team of explorers (which included two of his

sons) are believed to be the first Europeans to set eyes on the Rocky Mountains

north of New Mexico.

The town of Verendrye, North Dakota, is named for this

French-Canadian explorer. The town, with a Great Northern Railway station

located there, was originally named Falsen. Falsen station was established, and

evidently the town founded, in 1912. It was situated between Simcoe and

Karlsruhe, two other stations introduced by the railroad. The origin of the

name Falsen is not known.

|

| Ralph Budd, President of the Great Northern Railway (circa 1931). Author's collection |

In 1925, the Great Northern Railway sponsored the first of

two ambitious historical expeditions. The GN’s president, Ralph Budd, was an

enthusiastic amateur historian of the American northwest. He maintained an

extensive library of books and maps on the topic in his home in St. Paul,

Minnesota. The 1925 expedition was called the Upper Missouri Historical

Expedition. Special invitations were made up and delivered to a wide range of

authors, college historians, and politicians who might have a sympathetic

position about the expedition. While the event was clearly orchestrated as

something of an advertising campaign for the railroad, there is no doubt that

Ralph Budd possessed a sincere interest in observing and memorializing this

rich history.

The Upper Missouri Historical Expedition was conducted July

16-21, 1925. Prior to the event, the Great Northern Railway, on February 3,

1925, changed the name of Falsen station to Verendrye. The name of the town

soon followed suit. Both the Upper Missouri Historical Expedition and the

Columbia River Historical Expedition, conducted the following year, provided

extensive inspiration for stories to be told through the vehicle of the Empire Builders radio series. Continuity

writer Edward Hale Bierstadt (a nephew of famed western landscape artist Albert

Bierstadt) focused much of his effort during the radio show’s first season on

stories based in historical fact. It is almost a certainty that Ralph Budd

supplied Bierstadt with a complete set of booklets printed and distributed by

the railroad, in connection with the historical expeditions. The majority of

these booklets were written by Grace Flandrau (1886-1971).

|

| Cover of GN's booklet on the Verendrye Quest, published circa 1925 |

One title from the GN’s historical booklet collection,

authored primarily by Flandrau, is “The Verendrye Overland Quest of the

Pacific.” This booklet – and what appears to be a complete collection of all

the GN historical booklets referred to here – have been scanned as PDFs and can

be found at this remarkable web site, “Streamliner Memories,” maintained by Randal

O’Toole, a railroad historian and enthusiast from Oregon.

One of the goals of the two historical expeditions sponsored

by the Great Northern Railway was to commemorate the accomplishments of several

early explorers and other historical protagonists of the northwest. As the

company of participants in these historical expeditions traveled the line of the

GN on a special Great Northern passenger train, stops were made to honor the

key principals with speeches and, in some cases, permanent monuments. At

Verendrye, a monument to David Thompson was dedicated by the GN Railway during

the historical expedition, and speeches were made about both Thompson and

Verendrye. One such presentation was made by a man named Doane Robinson,

superintendent of the South Dakota State Historical Society. Mr. Robinson was

an acknowledged scholar on the topic of the Verendryes and their exploration of

the Dakota area. He also had a key part to play in bringing the so-called

“Verendrye Tablet” into the realm of other historians and scholars.

|

| Verendrye tablet, dug out of the ground near Pierre, South Dakota, in 1913. South Dakota State Historical Society photo |

It was a Sunday – February 16th – and at one point Hattie spotted something sticking out of the ground. She kicked at it and realized it was dense and did not easily move. The three soon dug it free from the ground. What they had was a lead tablet, about eight and a half inches long, six inches across, and about an eighth of an inch in thickness.

The kids did not realize the tablet had any historical

value, but to them it had scrap value. One account says George declared he

would trot it over to a print shop in town, which was always willing to buy

scrap lead. Before he could do this, however, fate stepped in, in the form of

two state legislators that George came across that evening. They took a gander

at the tablet, saw that it was something special, and promptly called in state

historian Doane Robinson, who was already a leading scholar on the life and

adventures of Pierre de la Verendrye. He immediately recognized the

significance of what the kids had discovered.

Some of the tablet was clearly prepared prior to the Verendrye

expedition, with additional text carved into the lead surface before it was

buried. Robinson was well-acquainted with the story of the Verendryes burying

the tablet. The text was mostly in either French or Latin. Robinson had it

translated. Some of the text indicated it was buried by Verendrye and his sons

on March 30, 1743.

|

| Both sides of a souvenir replica of the Verendrye tablet. The souvenir was also made of lead, but was just 3.25 by 2.5 inches. Author's collection |

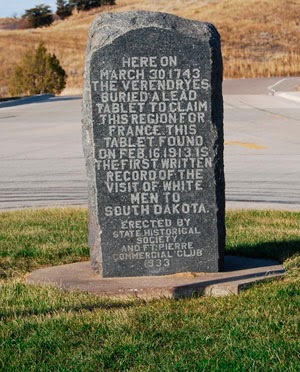

In 1933, the South Dakota State Historical Society placed a

monument on the site where the tablet had been discovered in 1913.

Another feature of the March 25, 1929, broadcast of Empire Builders was the appearance of a

guest performer and direct descendent of Pierre de la Verendrye: Miss Juliette

Gaultier de la Verendrye, a mezzo-soprano. She was a student of Vincenzo

Lombardi, one of Enrico Caruso’s teachers.

+and+George+O'Reilly+(R)+-+SD+St+Hist+Soc+photo.JPG)